One hundred years ago: the discovery of insulin

- oliviercourteaux

- Nov 15, 2021

- 3 min read

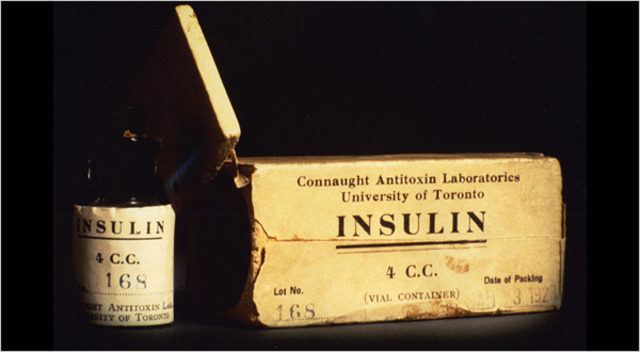

To celebrate World Diabetes Day, a brief reminder of the tremendous medical breakthrough achieved by four researchers in Toronto (Frederick Banting, Charles Best, John Macleod, and James Collip): the discovery of insulin, in 1921, which forever altered the way diabetes is being treated.

All began in 1920 when Frederick Banting (1891-1941), a trained physician and medical scientist approached his colleague, John Rickard Macleod, Professor of Physiology and Associate Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto, with a new idea: the treatment of diabetes with pancreatic extracts to regulate glucose levels. Macleod then introduced Banting to one of his students, Charles Best, so that the pair could conduct the appropriate experiments. In January 1922, James Collip, a biochemist, joined the team.

Why focus on the pancreas?

Simple!

Some of the food we eat is broken down before it reaches our intestines in the form of glucose. Glucose is then absorbed in the small intestine and makes its way to the bloodstream.

What about the pancreas?

The pancreas has two key functions. The first function is to produce digestive enzymes, which break down carbohydrates and proteins into our system. The second function, far more important for our story today, is to regulate blood sugar levels by secreting directly into the bloodstream a particularly important hormone: insulin.

When the pancreas fails to produce enough insulin or the cells in our body do not respond the way they should to the insulin produced (insulin resistance), we develop a condition called diabetes.

The key role of pancreas was formally identified in the late 1880’s, but the way to treat diabetes was not, until one day, in the summer of 1920, Banting and Best managed to isolate insulin after performing an experiment on two dogs. One the dogs was healthy, but the other suffered from diabetes. By injecting the newly isolated pancreatic secretion into the dog with diabetes, they successfully lowered its blood sugar levels. The experiment was a complete success.

In January 1922, the team performed the first clinical trial on a 14-year-old boy, Leonard Thompson. Leonard had been diagnosed with diabetes at the age of eleven and his prognosis was poor. He only weighted sixty-five pounds and his daily caloric intake barely reached 450, a far cry from the normal intake for a boy his age. Desperate, his parents brought him to Toronto and agreed to the clinical trial. On January 11, 1922, a young resident, Dr. Jeffrey, injected young Leonard with pancreatic extracts from an ox. The glucose level in the blood (glycemia) fell slightly, however the glucose level in the urines (glycosuria) remained far too elevated. The conclusion: the pancreatic extracts were neither pure nor stable enough. Two weeks later, purified extracts were injected and, within days, Leonard’s glycemia fell steadily. As for the glycosuria, it disappeared entirely.

In May, Leonard left the hospital, only to return in October, having gone into a diabetic coma. As it happened, his insulin intake was insufficient. By the time he was released for the second time, he had been put on insulin permanently.

By the end of 1922, some fifty patients suffering from severe diabetes were being treated successfully at Toronto General Hospital. The results of the first clinical trials were then published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, in March. Two months later, John Macleod presented the new treatment at the Association of American Physicians, in Washington DC. The following year, 250 physicians treated over 1 000 patients with insulin, both in Canada and the U.S. From then on, the new treatment made its way to other countries.

The discovery of insulin proved to be a major turning point in the history of medicine. The international community understood it all too clearly, for Banting and Macleod were rewarded with the Nobel Price of Medicine on October 25, 1923, barely eighteen months after their first clinical trial.

Frederick Banting declared, “Insulin is not a cure for diabetes; it is a treatment.” It may be so, but his (and his colleagues) discovery of insulin and its tremendous therapeutic potential, not only improved the medical odds for millions, but helped treat an insidious disease no one fully understood until then. And for that, we should all be grateful…

Komentarai